Fail Fast Philosophy

The fail fast philosophy centers on rapid testing, learning, and iteration. It discourages prolonged perfectionism prior to release and instead favors early experiments under real-world conditions to reveal what works and what does not while mistakes remain low-cost. Effective fail-fast practice requires intelligent failure: systematic analysis of each setback to answer why it failed, what was learned, and how future attempts should change. Turning individual lessons into shared knowledge through structured debriefs and stakeholder communication converts isolated mistakes into collective advantage.

Organizational Culture and the Blame Game

A culture that equates failure with punishment inhibits the transparency required for effective learning. Psychological safety is a prerequisite for fail-fast methods: employees must be able to disclose errors without fear of retribution. Leadership must model curiosity about causes rather than searching for culprits, incentivize reporting and analysis, and embed continuous experimentation into routine practice. Development and public service sectors illustrate the gap between rhetoric and reality: despite broad endorsement of learning from failure, many institutions fail to apply systematic methods. Leaders who focus on understanding root causes and encouraging iterative reporting unlock the transformative potential of failing fast.

Designing for Failure

Integrating fail-fast thinking into product design accelerates learning cycles and reduces costly redesigns. When teams anticipate possible failure modes from the concept stage onward, they compress development timelines and improve final product robustness. Designing to fail fast means embedding rapid prototyping, low-cost pilots, and customer validation steps into the workflow, so that lessons emerge early and inform the next iteration. Differentiating failure types and their expected impact enables teams to prioritize experiments that maximize learning while minimizing downstream harm.

Types of Failures and Strategic Significance

Consequently, failures vary in strategic weight and informational value. High-visibility projects championed by senior leaders carry symbolic importance and produce lessons that propagate across organizations, while small-scale experiments can yield disproportionately valuable scientific or product insights. In research-intensive fields, the informational contribution of a failed experiment often matters more than its cost or scale. Applying fail-fast methods strategically requires assessing a project’s potential learning value and designing experiments to surface transferable insights rather than merely measuring financial loss.

Benefits and Implementation

Fail-fast practices deliver measurable advantages when implemented deliberately and collectively.

- Maximizing resource efficiency. Early termination of unpromising ideas conserves time, capital, and human effort, which is critical for resource-constrained teams.

- Integrating customer feedback. Rapid experiments produce real‑time user input that guides product-market fit and feature prioritization.

- Accelerating decision-making. Tools like the Minimum Viable Product reduce analysis paralysis and enable faster, evidence-based choices.

- Stimulating innovation. A culture tolerant of intelligent failure encourages creative exploration and continuous iteration, which is vital in rapidly changing markets.

Accordingly, implementation requires more than ideology. It demands governance for rapid experimentation, mechanisms for capturing and disseminating lessons, leadership that rewards transparent reporting. When organizations institutionalize these structures and normalize constructive responses to failure, failing fast becomes a disciplined engine for sustainable innovation.

How to Implement a Fail‑Fast Approach

In rapidly evolving technology markets, adaptability is a core determinant of organizational survival. Embracing fail‑fast practices lets teams surface weaknesses early, correct them efficiently, and preserve market relevance by shortening feedback loops and accelerating learning.

Delegation and the Learning Culture

Clear delegation is essential. Every team member must understand specific objectives and their responsibilities for spotting, analyzing, and resolving faults. When structured experiments are a shared duty, the organization as a whole becomes quicker to detect problems and more resilient in response. Failing fast is not a license for disorder; it is the disciplined application of iterative learning cycles to drive continuous improvement and measured risk taking.

FMEA: Traditional Failure Analysis

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) has been a long-standing, methodical framework for identifying and prioritizing potential failure points, originating under U.S. military standards and subsequently adapted in the automotive industry. FMEA formalized the idea that systematic analysis of possible failures strengthens design outcomes. Its limitations include dependence on detailed design inputs, heavy reliance on expert judgment, and the need for cross functional teams, which can make it time consuming and costly to run and maintain. As a result, FMEA is often less practical in the early, conceptual stages of development.

FFDM: A Conceptual, Data-Driven Alternative

The Function Failure Design Method (FFDM) advances failure analysis by shifting the focus from physical components to functional behavior, making it applicable during conceptual design. FFDM reduces subjectivity by leveraging archived failure data rather than relying solely on expert intuition, shortening analysis time and improving repeatability. It can be adopted either as a comprehensive design methodology or as a standalone failure analysis tool. By mapping functional requirements to historical failure knowledge, FFDM helps designers anticipate and mitigate problems earlier in the lifecycle, embodying the fail fast imperative to learn from past mistakes systematically.

Contact us today to learn how LA NPDT can assist in realizing your project.

Applying Fail Fast in SMEs

For small and medium-sized enterprises, failing fast is fundamentally a mindset as much as a method. In volatile markets, rapid experimentation, quick absorption of lessons, and continuous adaptation are survival skills. SMEs benefit from learning across a spectrum of failure types: experimental setbacks, innovation missteps, limited pilot failures, intelligent failures that reveal useful insights, and observational learning from others’ mistakes.

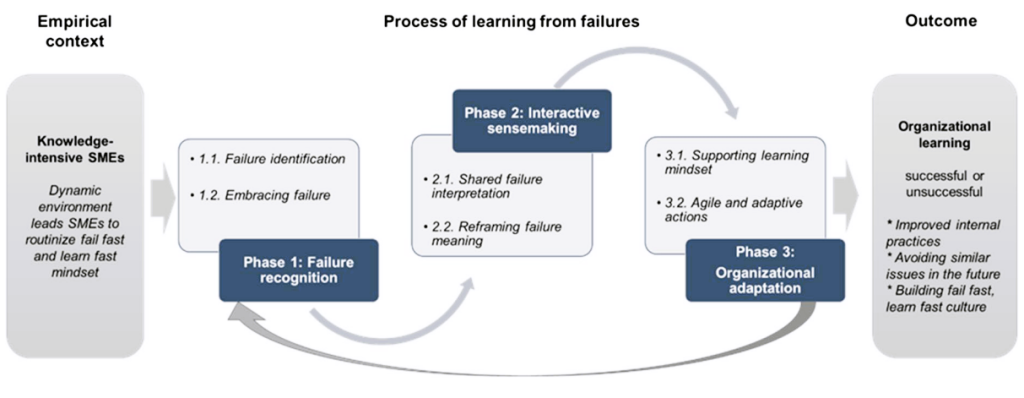

Figure 1. Conceptualizing the process of learning from failure in SMEs

Although often unplanned, these failures deliver practical knowledge that refines decision‑making and accelerates organizational learning.

Implementation Essentials

Operationalizing fail‑fast requires more than tolerance for error; it demands structure: clear governance for rapid experiments, mechanisms to capture and disseminate lessons learned, leadership that rewards transparent reporting, and cross‑functional teams aligned on short learning cycles. Tools such as low‑cost pilots, MVPs, archival failure databases, and routine post‑mortems transform isolated errors into reusable knowledge and guide subsequent iterations.