The discipline of human factors originated during World War II, when psychologists investigated how excessive mental strain led to pilot mistakes, reduced alertness, and hindered learning. These early findings revealed a key truth: systems break down when they overwhelm the human mind.

Since then, HFE has expanded into consumer electronics, healthcare, telecommunications, cybersecurity, and digital experiences. Across all these fields, cognitive load remains a defining factor that shapes usability, safety, and overall performance.

Human Evolution, Technology, and the Growth of Cognitive Load

For most of human existence, people lived in environments with relatively predictable mental demands. Tools were shaped around human abilities, keeping cognitive load manageable. Modern technology has dramatically disrupted this equilibrium.

Today, nearly every object and interface is intentionally designed. When designers add unnecessary steps, confusing layouts, or too many choices, they increase cognitive load. Users feel this immediately. When someone says, “This is difficult to use,” they’re reacting to poorly managed cognitive load.

Effective design reduces mental effort; poor design amplifies it.

Core Principles of Human Factors Engineering

At its foundation, HFE is guided by one principle: build systems that align with human strengths and limitations. Because working memory has strict boundaries, every design choice affects cognitive load.

To achieve this, HFE draws on cognitive psychology, experimental psychology, industrial engineering, biomechanics, and organizational psychology. Together, these fields help designers minimize cognitive load across interfaces, workflows, controls, and environments.

In practice, software teams manage cognitive load throughout the entire development process – from requirements gathering to usability testing and release. When cognitive load is intentionally controlled, products become easier to learn, quicker to use, and less prone to errors.

Why Designers Must Address Cognitive Load Early

As technology advances, systems naturally become more complex. Without deliberate effort, cognitive load increases. Fixing these issues after launch is far more expensive and time-consuming than addressing them early.

Early design choices determine:

- How much mental effort must users expend

- Whether workflows feel intuitive or draining

- Whether products support long-term human well-being

Teams that prioritize cognitive load from the start build products that scale without overwhelming users.

What Happens When Cognitive Load Becomes Excessive?

When cognitive load surpasses human limits, problems surface quickly – especially in digital products and online commerce:

- Users abandon onboarding flows because the mental effort feels too high

- Shoppers leave items in their carts when decision fatigue spikes

- Support teams receive complaints about features that create unnecessary mental strain

- Users quietly churn when the effort outweighs the perceived benefit

Even worse, high cognitive load undermines confidence. People often blame themselves instead of the product – an unmistakable sign of design failure.

Usability Evaluation

To avoid these issues, usability assessments must identify sources of excessive cognitive load. Effective evaluations measure not only task completion but also perceived effort, confusion, and fatigue.

Teams that assess cognitive load early resolve usability problems faster and more affordably. Those that ignore it face higher development costs, lower user satisfaction, and greater risk – especially in safety-critical environments.

Understanding Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive load refers to the mental effort required to perform a task. As it increases, users must devote more attention, memory, and decision-making resources. Lower cognitive load enables smoother, more confident action.

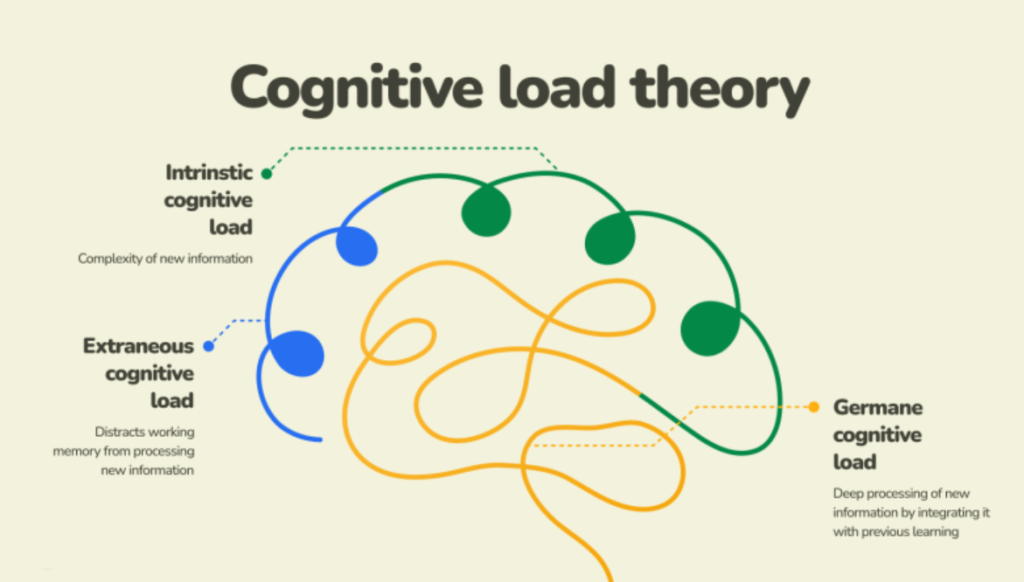

Cognitive Load Theory identifies three types:

- Intrinsic load – inherent complexity of the task

- Extraneous load – unnecessary mental effort caused by poor design

- Germane load – mental effort that supports learning

Figure 1. Cognitive load theory (Source – www.thealien.design/insights)

Contact us today to learn how LA NPDT can assist in realizing your project.

In UX, the primary goal is to reduce extraneous load, since design choices directly influence it.

What Cognitive Load Means in UX Design

In UX, cognitive load determines how easily users interpret interfaces, understand choices, and take action. Because working memory is limited, interfaces with too many options, vague labels, or confusing flows dramatically increase cognitive load.

When this happens, users hesitate, disengage, or abandon tasks. Designers who manage cognitive load create experiences that feel seamless rather than overwhelming.

Proven Strategies to Reduce Cognitive Load

- Simplify Interactions

Break complicated processes into smaller, manageable steps to reduce mental effort and improve clarity.

- Make Information Easy to Locate

Use clear labels, logical grouping, and concise wording to reduce search-related load.

- Apply Strong Visual Hierarchy

Visual hierarchy directs attention and reduces perceptual load by highlighting what matters most.

- Minimize Context Switching

Stable, focused workflows prevent sudden spikes in cognitive load.

Applying Theory in Real Products

- User Testing That Measures Cognitive Load

Teams should evaluate how mentally demanding tasks feel – not just whether users complete them.

- Progressive Disclosure

Reveal information gradually, only when it becomes relevant, to keep cognitive load manageable.

- Personalization

Tailor experiences to remove irrelevant choices and reduce decision fatigue.

Cognitive Load as a Key UX Metric

Cognitive load directly affects usability, satisfaction, retention, and conversion. Designers who monitor it create interfaces that align with natural human decision-making.

Low cognitive load builds confidence; high cognitive load creates hesitation – even in visually polished designs.

Human Factors, UCD, and Cognitive Load

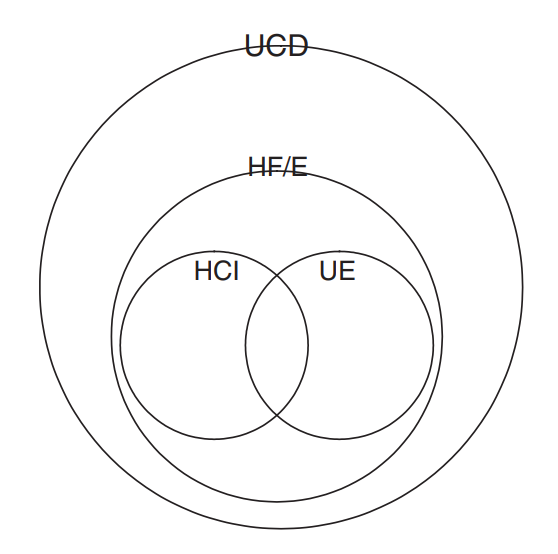

Within User-Centered Design (UCD), Human Factors Engineering (HFE) includes human–computer interaction (HCI) and usability engineering (UE). All these disciplines share a common mission: minimize cognitive load in human–machine interactions.

Figure 2. Relationships among UCD, HF/E, HCI, and UE (Source – James R. Lewis IBM Software Group, Boca Raton, Florida, U.S.A.)

Product Operations and Cognitive Load

Product Operations teams increasingly apply cognitive load principles internally:

- Reducing mental burden for product managers

- Streamlining workflows and decision paths

- Automating tasks that create unnecessary effort

Lower internal cognitive load leads to better efficiency, clarity, and job satisfaction.

Cognitive Load vs. Cognitive Demand

To distinguish the two:

- Cognitive load is the effort required to understand what’s on the screen

- Cognitive demand is the effort required to decide what to do next

Weak hierarchy increases cognitive load; unclear calls to action increase cognitive demand. Effective design minimizes both.

Designing for Perception by Managing Cognitive Load

Key principles:

- Emotional clarity reduces mental strain

- Clear benefits lower interpretive load

- Social proof reduces evaluative load

- Consistency prevents expectation-related load